In the US, the stories of a select few Black women — Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Rosa Parks, Ida B. Wells, to name a few — seem to circulate on a regular rotation in school classrooms, inspirational calendars and social media memes. While these women’s contributions to history are incredibly important, there are countless other Black women who are less known but who are equally significant in terms of fully understanding the American experience.

“Their stories need to be told,” say Daina Ramey Berry PhD, chair of the history department at the University of Texas at Austin, and Kali Nicole Gross PhD, professor of African American Studies at Emory University. The two women are coauthors of the book A Black Women’s History of the United States. “Black women are true torchbearers of democracy,” explains Dr. Gross. “Black women have been demanding justice and liberty and have fought for it in ways great and small.”

History in the US (and much of the world) has largely been written by white men, with whiteness at the center, but the profiles here aim to reframe the stories, placing a wide range of Black women firmly at the heart. For this article, Drs. Berry and Gross thoughtfully curated the stories of five women to add to the narratives that we’re already familiar with.

While these women accomplished remarkable things, they were also remarkable for their humanity — for simply surviving despite unrelenting oppression. By learning about their experiences, we can gain new perspectives to understand and celebrate the role of Black women throughout America’s existence. Hopefully they will lead you to wonder: Who else has been left out of the history books? What can we learn from their stories? And how can we make space for the diverse narratives of Black women that are yet to be told?

The name to know: Isabel de Olvera, explorer, early 1600s

Her story in brief:

Isabel de Olvera was born in Querétaro, Mexico, in the late 1500s to an African father and an Indian mother. As a young, unmarried, free mixed-race woman in 1600, she sought permission and protection from the mayor of Querétaro to join an upcoming expedition to New Spain (or present-day New Mexico, Arizona and Florida). Although historians are not sure of her motives — some records suggest that she may have been hoping to assist recently settled families at her final destination — her deliberate preparations for the journey were documented.

de Olvera petitioned the mayor to provide her with written permission proving she was indeed a free woman. Because she was Black, she knew she could be claimed as property by men she encountered on her journey. Her appeal to the mayor ended with this simple but clear declaration: “I demand justice.”

After an eight-month legal process, which included sworn testimony from witnesses to prove her independence and her worthiness, de Olvera was eventually permitted to go on the expedition. The journey covered nearly 1400 miles, crossing multiple rivers, deserts and mountain ranges. While some records of the hardships exist, the exact details of where and when de Olvera went, as well as what happened next in her life, are left to speculation. “I wish we knew more, and we did a whole year of research on her,” says Dr. Berry. “We think about how many miles she might have traveled, and we recognize the bravery of what she did at that time”.

Why her story should be told:

Simply put, Isabel de Olvera’s existence as a free woman in the 1600s challenges the narrative that the Black experience in America began only when Africans were forcibly brought to this country and enslaved. Her journey is also among the earliest recorded instances of Black people fighting for liberty in North America, an act of resistance that is repeated throughout history.

“Freedom is always fraught, and Black women are always demanding justice to be treated like human beings,” says Dr. Berry. “And Isabel is one of the first women that we can identify who is doing just that.”

The name to know: Monemia McKoy, mother of twins Millie and Christine, 1830’s – ?

Her story in brief:

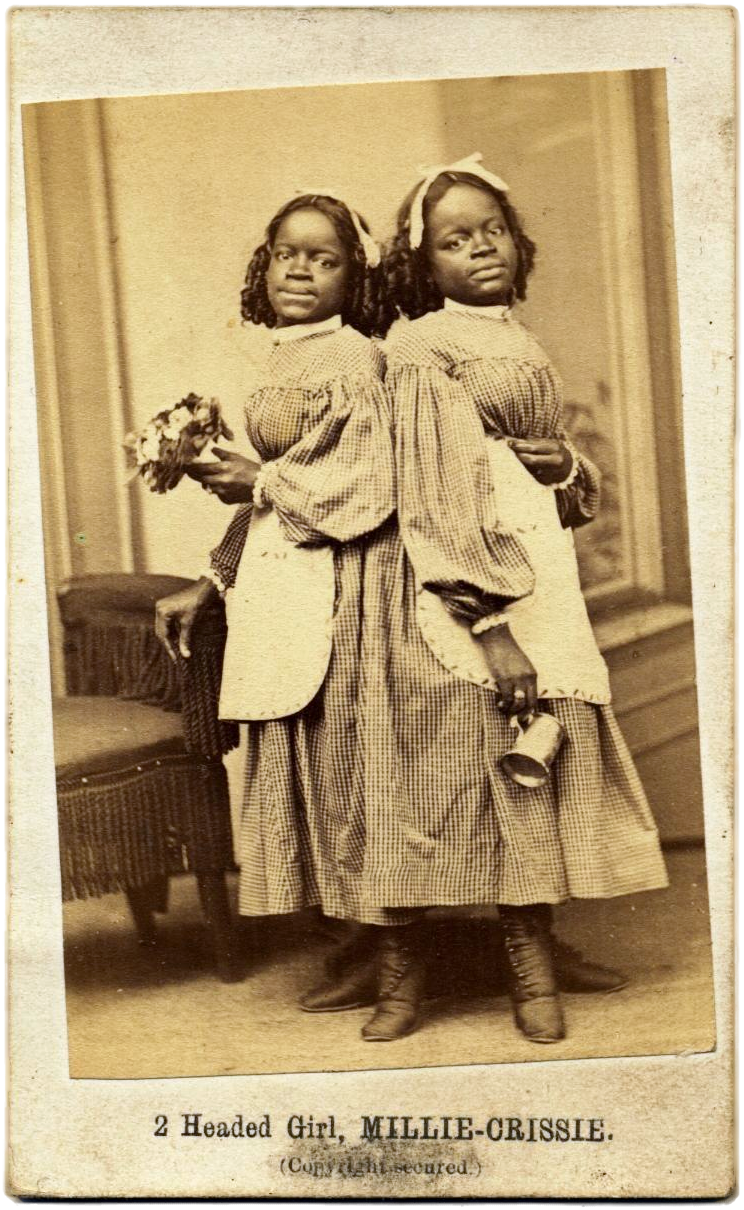

Enslaved couple Monemia and Jacob McKoy lived in North Carolina in the mid-19th century. In 1851, Monemia — already the mother of 7 children — gave birth to conjoined twins Millie and Christine.

While all enslaved parents lived with a constant fear of being separated from their children at the auction block, that threat was more pronounced for the McKoys because Millie and Christine were considered “genealogical wonders”. The girls each had their own limbs but were joined at the pelvis. Throughout their lives, they were sold, kidnapped, endured horrific and invasive medical exams, and forced to perform in sideshows.

Despite her circumstances, Monemia fought endlessly for her children. As toddlers, Millie and Christine were sold, stolen and sent to Europe to perform. “In a staggering act of Black motherhood, Monemia travelled there, along with the girls’ owner and a detective,” wrote Drs. Berry and Gross in their book. “The three bought tickets where the 6-year-old twins were scheduled to perform. When Monemia was reunited with her daughters in the front row, she fainted.”

Following this reunion in the late 1850’s, the court in Birmingham, England, granted full maternal rights to Monemia. Drs. Berry and Gross want to underscore how profound that moment was: “For a rare moment in 19th-century history, a Black mother was reunited with her daughters because she was their mother, rather than taken away from them through the yoke of slavery,” they wrote.

Monemia and her daughters returned to the US where the twins received an education and continued to perform throughout the world. Records show the twins were eventually able to purchase the property where they were born, providing housing for their parents and siblings. Millie and Christine died within hours of each other at the age of 61 in 1912.

Why her story should be told:

Monemia McKoy’s fierce efforts to protect her children foreshadows both historic and current examples of Black motherhood. “The legacy of Black motherhood is strength,” says Dr. Berry, drawing a line from Monemia to the mothers of Emmett Till, Trayvon Martin and Breonna Taylor and other Black mothers who’ve been thrust into the spotlight. “I see Monemia in all these other mothers on television who don’t want to be there but are fighting for their child’s life or fighting for recognition and honor in their death,” adds Dr. Berry.

Her story in brief:

Although born into slavery in Alabama and assigned male at birth, by the age of 26 Frances Thompson was freed and living according to her own gender identity in a booming Black community in Memphis, Tennessee. She kept her face clean-shaven, wore brightly colored dresses, and took in washing for pay. Then, during the deadly Memphis Riot of 1866, Thompson and her roommate, a Black woman, were brutally robbed and gang-raped by several white men, including two police officers.

Thompson and other assaulted women boldly testified at a committee hearing held by the US Congress, and she stated that she and her roommate did not consent. Her testimony became infamous throughout the South and led to 10 years of persecution for her gender identity, harassment and accusations, including claims that she ran a brothel. Thompson was jailed in 1876 for “cross-dressing” and died later that year. But Gross and Berry note in their book that even though “behind bars, she suffered but [she] never lost her fight, answering rude questions about her gender by responding, ‘None of your d____ business’”.

Why her story should be told:

“What is so powerful is that Thompson and the other women who testified go on record to say they did not consent,” explains Dr. Gross. “This is huge for Black women because just a few years before, they didn’t have the rights to their own bodies as enslaved women. Even free Black women were often raped and there was no justice available.” What’s more, with Thompson’s example “we start to see Black women beginning to reclaim their bodies and try to actualize citizenship to protect Black womanhood,” adds Dr. Gross.

Another reason why Thompson’s story is important is the concept of “transcestry,” an idea that Dr. Gross credits to LGBTQ activist CeCe McDonald, which seeks to tell the earliest stories of transgender people living according to their gender identity. “Just to acknowledge Thompson’s existence is powerful,” as Dr. Gross puts it. “A woman in 1866 fought bravely to live her truth against unthinkable kinds of peril and odds, and we need to honor that so future generations know and see themselves reflected in our experience.”

Her story in brief:

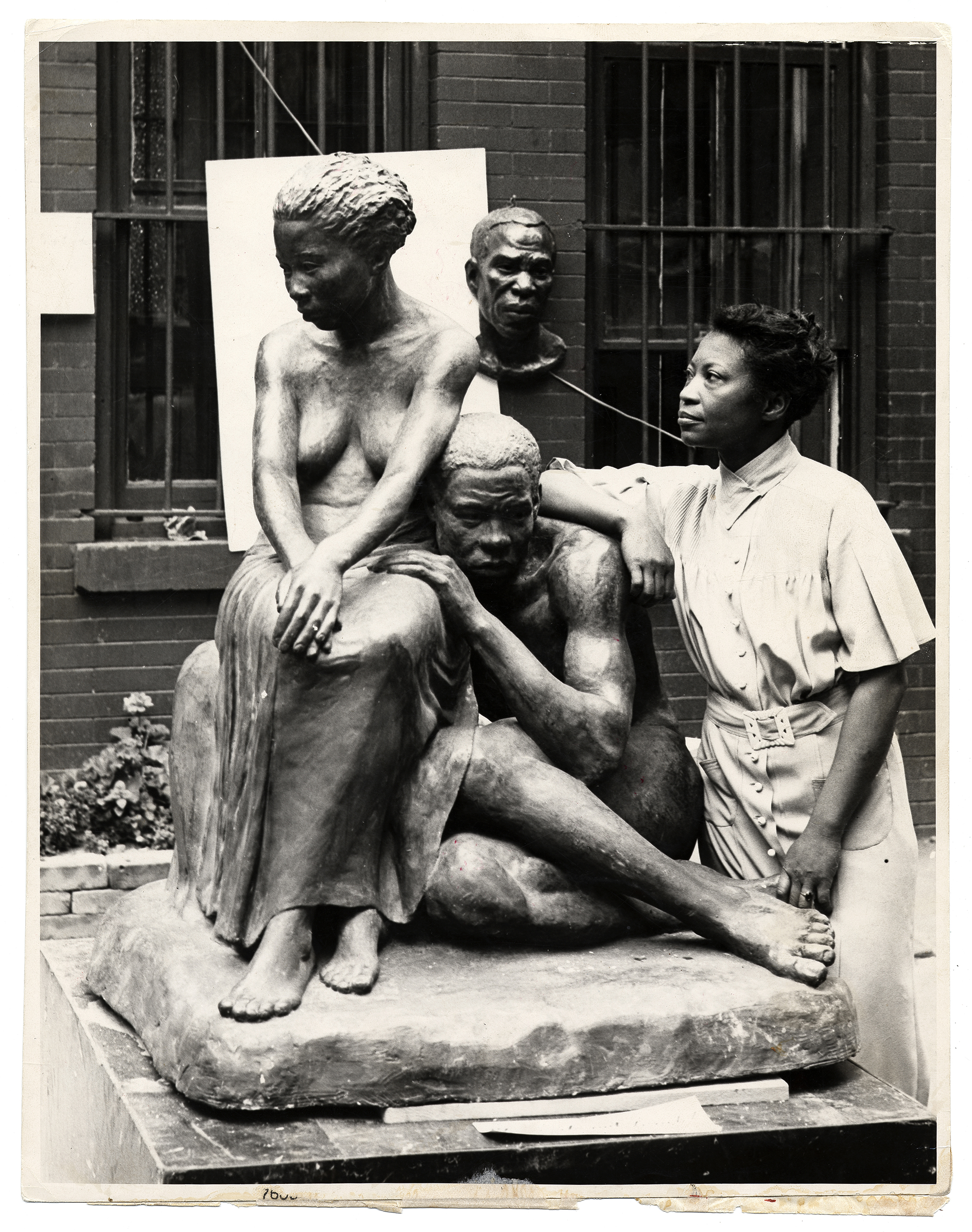

Born to the family of a conservative Methodist minister in Green Cove Springs, Florida, Savage exhibited a passion and a talent for art from an early age, in particular for molding objects out of clay. But her father discouraged her creations through corporal punishment, claiming they were sinful. “Father licked me five or six times a week and almost whipped all the art out of me,” Savage recalled in interviews.

Savage put aside her art and got married. Shortly after she gave birth to her only child, her husband passed away. After another marriage and an inspiring encounter with a local potter, Savage left her husband and joined the Great Migration, heading to New York in 1921. There, she reinvented herself, shaving 10 years off her age, referring to her then-14-year-old daughter as her sister, and contributing her talents to the creation of a new Black cultural identity during the Harlem Renaissance.

Her artistic career was marked by incredible highs and lows. Savage battled poverty and racism, both of which limited her opportunities. Yet at the same time, as Drs. Berry and Gross wrote, “Augusta’s life was steeped in the blossoming African American cultural revolution taking place.” She wrote poetry and hosted Black literary luminaries such as Dorothy West, Claude McKay, Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston in her overcrowded apartment, while sculpting busts of people in her community as well as leaders like Marcus Garvey.

Savage’s greatest professional accomplishments include traveling to study in Paris, being the first Black artist elected to the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors, and receiving a commission to create art for the 1939 New York World’s Fair (a 16-foot-high creation entitled Lift Every Voice, which was the inspiration for what became known as the Black National Anthem of the same name).

Why her story should be told:

Savage’s story is defined by her talent, struggle, passion, self-determination and celebration of Blackness through her art. “Her artwork, while it was very much rooted in the experience of Black people, wasn’t just about struggle and oppression,” says Dr. Gross. “It’s about embracing who we are in a much more expansive way and not just in resistance to white people.”

The ups and downs of Savage’s life are an equally important piece of her legacy, according to Dr. Gross. “She’s a perfect model for showing how the kinds of progress that Black women make isn’t linear — it ebbs and flows. That, for me, is a testament to our humanity.”

Her story in brief:

Barbara Jordan was born in 1936, in Houston, Texas to a teacher and Baptist preacher. A Career Day speech at her segregated high school given by lawyer Edith Sampson, the first Black American delegate to the United Nations, inspired Jordan to become an attorney.

Before entering politics, she taught political science at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. She was elected to the Texas State Senate in 1966. To say that her election was exceptional is an understatement: She was the first Black woman elected to the State Senate, and the last time a Black person had been elected to that office was nearly a century earlier (in 1883). During Jordan’s time there, she helped pass the state’s first minimum wage law and was instrumental in creating its Fair Employment Commission.

Then, in 1972 — the same year that Shirley Chisholm ran for President — Jordan was elected to the US House of Representatives. Her political style became juxtaposed with Chisholm because of the timing and the difference between their approaches. Chisholm’s politics were influenced by Marcus Garvey. Her slogan was “Unbought and Unbossed”, and she called for a “bloodless revolution” at the 1972 Democratic National Convention. Meanwhile, Jordan opted to work more quietly within the system. She was a well-liked and effective legislator. “In moving past the stringent racism of her white colleagues, Barbara managed to earn their respect,” wrote Drs. Berry and Gross.

But Jordan’s non-combative style did not mean she shied from speaking truth to power. Her impressive oratory skills earned her acclaim in Congress during the waning days of the Nixon Administration. “Barbara, the daughter of a Baptist minister, took to the floor of Congress and delivered a stirring address to demand that the country’s elected officials do what was right and impeach the president,” wrote Drs. Berry and Gross.

Why her story should be told:

Barbara Jordan’s Congressional career pushes back against the assumption that Black political action is monolithic and exists solely in resistance to white supremacy. Not all Black politicians are radical or even progressive, according to Drs. Berry and Gross, who point out that today not all people of color identify with “the Squad” in Congress.

“There are masses of Black folks who are much more conservative and don’t necessarily want to have every conversation be about race and anti-Blackness,” explains Dr. Gross. “There are people who care more about just getting food on the table, having access to decent employment and fair housing.” Dr. Gross goes on to say that while Jordan “was not a radical Black politician, she also wasn’t in denial. She fought for voting rights and tried to safeguard the rights of citizenship for Black people.”