One of the largest structures ever found, a newly discovered crescent of galaxies with a length of 3.3 billion light-years challenges some of astronomers’ most basic ideas about the nature of the universe.

The Giant Arc is a vast collection of galaxies, galaxy clusters, and a great deal of gas and dust. It covers around a fifteenth of the observable universe and is 9.2 billion light-years away.

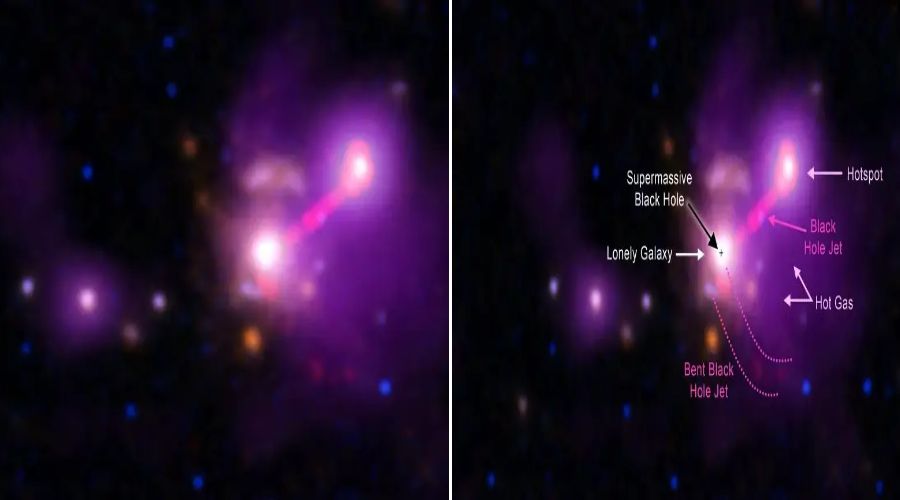

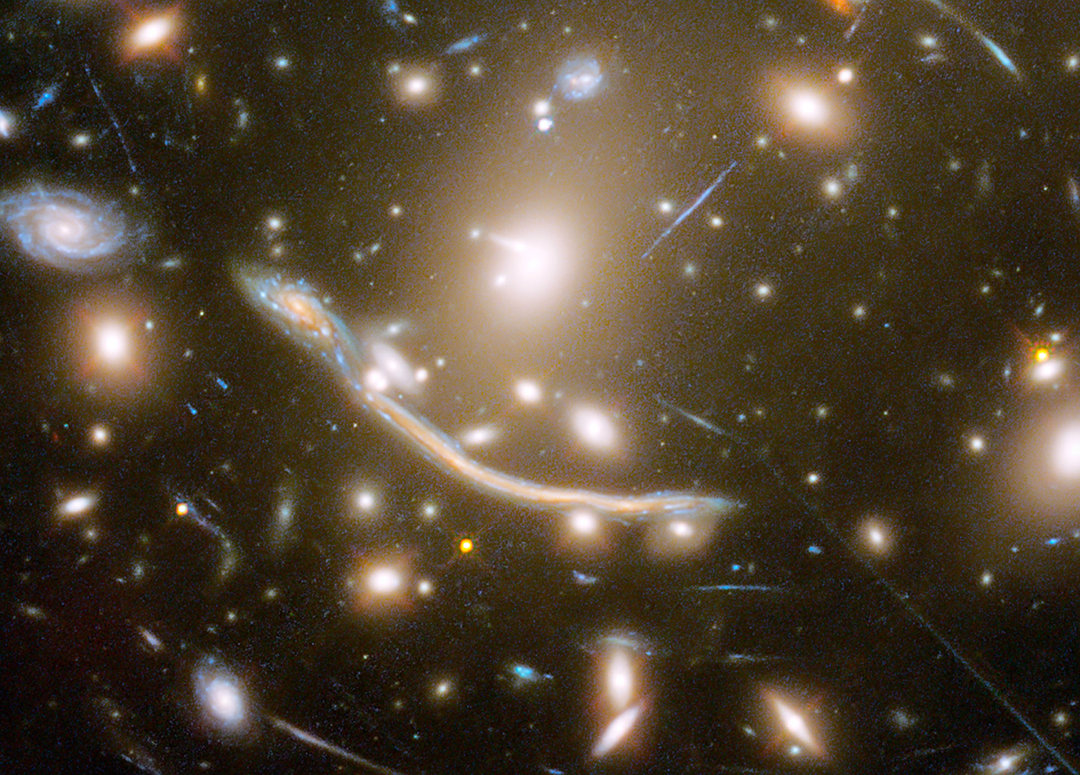

According to Alexia Lopez, a cosmology doctorate candidate at the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan) in the UK, its finding was “serendipitous.” Lopez was utilizing light from about 120,000 quasars, which are far-off luminous centres of galaxies where supermassive black holes consume matter and release energy, to map objects in the night sky.

Between us and the quasars, this light travels through matter and is absorbed by various elements, leaving behind telltale signs that can be very useful to researchers. Lopez in particular employed magnesium’s marks to measure the distance to the separating gas and dust as well as the substance’s

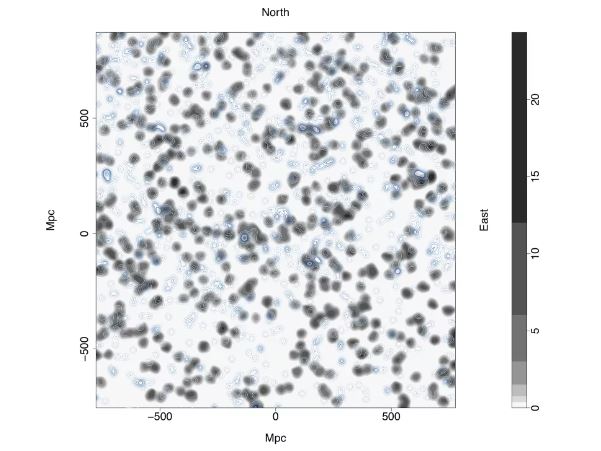

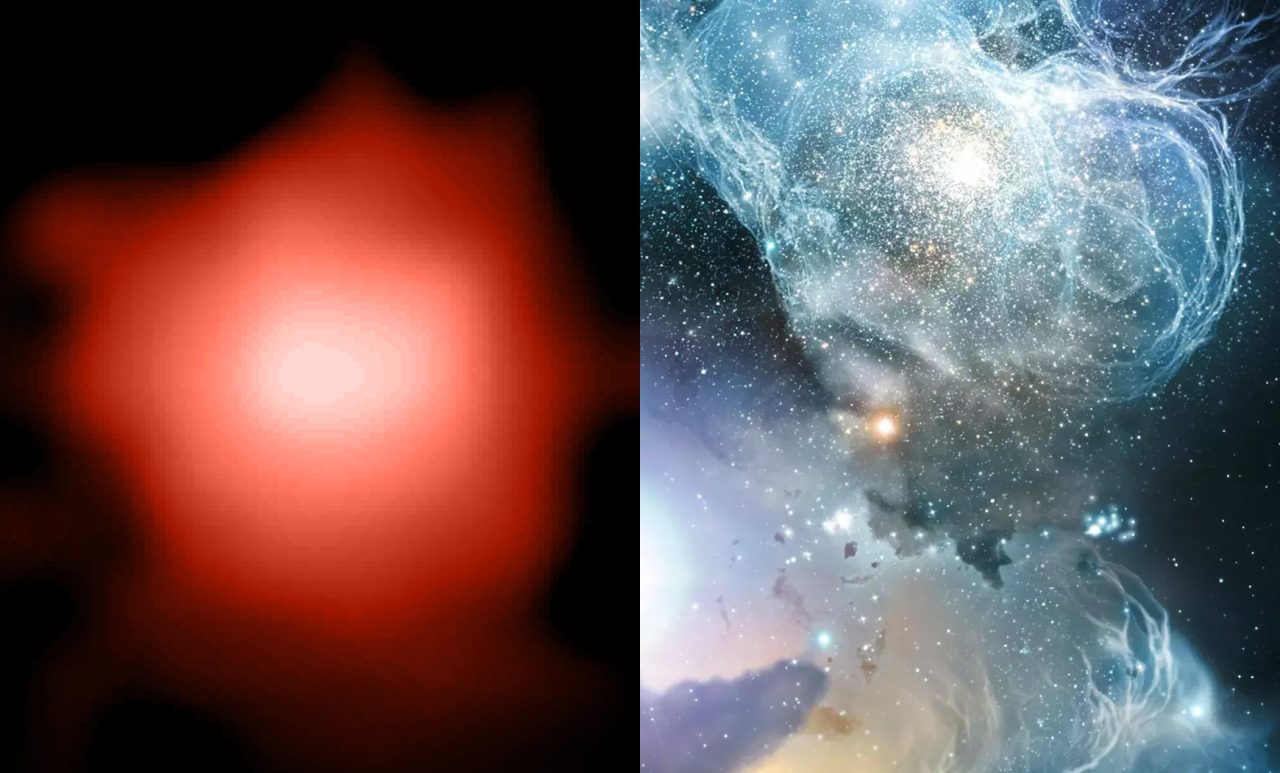

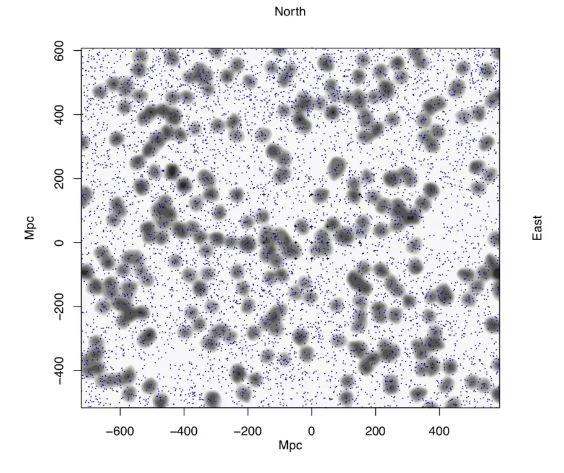

Giant Arc. Magnesium-absorbing regions are indicated by grey areas, which reflect the dispersion of galaxies and galaxy clusters. Background quasars, also referred to as spotlights, are the blue dots. (Photo courtesy of Alexia Lopez/UCLan.)

According to Lopez, the quasars function in this way, “like spotlights in a dark room, lighting this intervening stuff.” Over the course of the cosmic maps, a structure started to take shape. Lopez said that there was “kind of a hint of a vast arc.” I can still picture myself approaching Roger Clowes and saying, “Oh, look at this.”

Clowes, her doctoral adviser at UCLan, suggested further investigation to guarantee it wasn’t an accident or a data trick. After doing two different statistical tests, the researchers determined that there was less than a 0.0003% probability that the Giant Arc wasn’t real. They presented their findings at the American Astronomical Society’s 238th virtual meeting.

The structure of the Giant Arc is shown in grey, with nearby quasars superimposed in blue. There is a tentative relationship between these two datasets. (Image credit: Alexia Lopez/UCLan.

But the discovery challenges a fundamental belief about the universe and will rank among the cosmos’ greatest discoveries. The cosmological principle, which states that matter is more or less evenly dispersed throughout space at the largest scales, has been a long-standing tenet of astronomy.

The Sloan Great Wall and the South Pole Wall, both of which are dwarfed by even larger cosmic structures, are smaller than the Giant Arc. Over the years, large-scale structures have been found, according to Clowes, who spoke with Live Science. They seem to defy the cosmological principle because they are so enormous.

The fact that such massive entities have gathered in particular places of the universe suggests that matter may not have been distributed evenly throughout the universe. However, Lopez added, the current standard model of the cosmos is based on the cosmological principle.

“If we’re finding it not to be true, maybe we need to start looking at a different set of theories or rules.”

Lopez doesn’t know what those theories would look like, though she mentioned the idea of modifying how gravity works on the largest scales, a possibility that has been popular with a small but loud contingent of scientists in recent years.

The South Pole Wall’s founder, Daniel Pomarède, a cosmographer at Paris-Saclay University in France, agreed that the cosmological principle should put a theoretical limit on the size of cosmic things.

Some research has suggested that structures should reach a certain size and then be unable to get larger, Pomarède told Live Science. “Instead, we keep finding these bigger and bigger structures.”

Yet he isn’t quite ready to toss out the cosmological principle, which has been used in models of the universe for about a century.

“It would be very bold to say that it will be replaced by something else,” he said.

Soucre: news.sci-nature.com