Scientists have uncovered a rare find at the deepest point off Australia’s coast, which offers a remarkable glimpse into an unknown world.

A group of scientists have landed the deepest fish ever caught off Australia’s coast.

The team reeled in two unknown and possibly as yet undiscovered species of snailfish from a depth of 6177m, roughly 370 kilometres off the coast of Perth.

It was part of a study by the newly formed Minderoo and University of Western Australia (UWA) Deep Sea Research Centre.

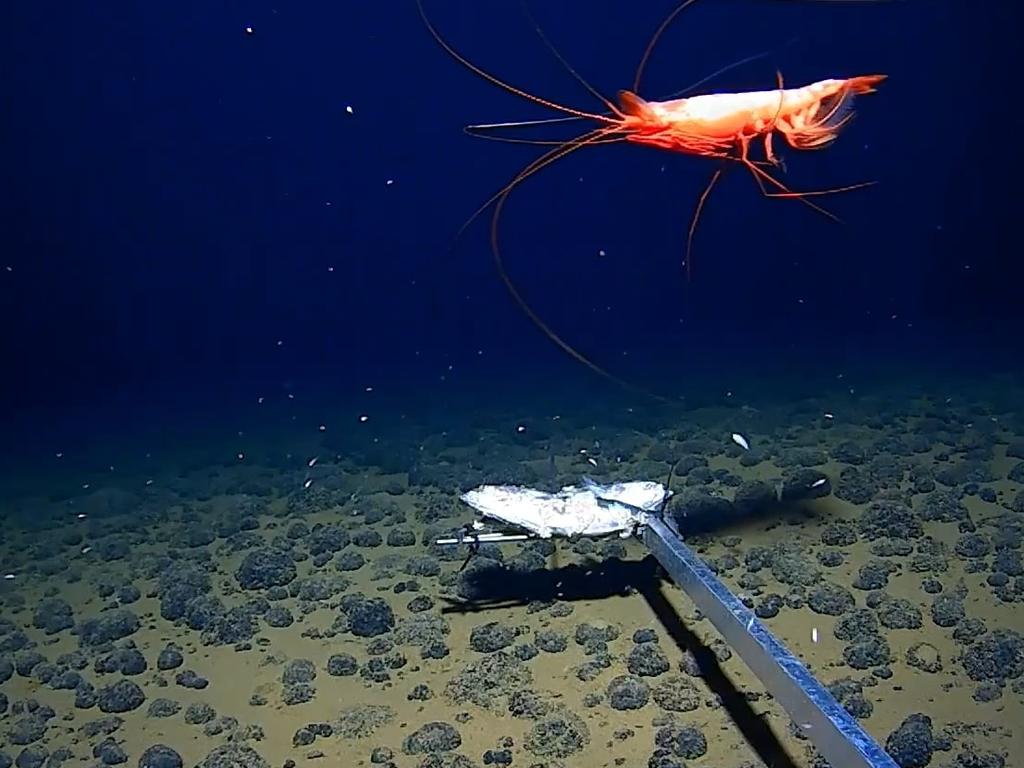

Going by the saying: “If it ain’t broke don’t fix it”, the team used a yabby trap from a local bait shop to land the prize – attached to a $100,000 deep sea monitoring device.

The device also provides video footage and other data from the bottom of the ocean, giving scientists a rare window into an unknown world.

Marine scientist and UWA postdoctoral fellow Todd Bond said he was surprised to discover after the very first deployment to the ocean floor they had caught not one, but two fish.

“This was the very first scientific deployment using that gear and we just happened to snag two fish, which was really, really cool,” Dr Bond said.

Snailfish are found all over the world and have the greatest depth range of any fish. They exist from just below the surface to the Mariana Trench, the deepest spot on earth, at just over 8000m.

They have a different type of flesh than other fish, making them gelatinous and delicate when brought to the warmer surface temperatures.

“It’s really important that when they do come up on deck we work with them very carefully to maintain their physical appearance, so we put them in ethanol and then put them in the fridge to keep them cold,” Dr Bond said.

The aim of the trip was specifically targeting the deepest location off mainland Australia – the Diamantina Fracture Zone.

“We were heading out there to document the biology, the geology and the water chemistry out there, essentially to understand the deep sea,” Dr Bond said.

The team use steel weights to sink their monitoring devices, which measure roughly a metre across, to the bottom of the ocean.

Attached is one trap for fish and another for ocean-floor dwelling crustaceans called amphipods.

“We deploy this system off a ship, it sinks to the bottom of the ocean and it sits there for about eight hours,” Dr Bond said.

“When we’re ready to tell it to come home, we send an acoustic ping, which basically tells it to drop the weights and then it floats to the surface where we pick it up.”

The large amount of data collected by the team will be pored over and compared to other readings and species around the world.

“We have current sensors and conductivity and temperature and there’s some really incredible things going on in terms of currents around this part of the world,” Dr Bond said.

“So we have quite a multidisciplinary team looking at all facets of this voyage and the things that we’ve collected.”

Dr Bond explained one of the things he was most excited to explore was the relationships between amphipods, in different extreme depth zones around the world.

“Obviously describing fish and having new species and understanding the rich diversity of animals that we’re finding off the deep sea of Australia, which has never been explored before, is very cool and very interesting,” he said.

“But the connectivity and setting it in a global context is the most exciting and will put this centre and this part of the world on the map in terms of deep sea science.”