A team of archaeologists from the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen, the Lower Saxony State Office for Heritage, and Leiden University has unearthed a nearly complete skeleton of the straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus), an extinct species of elephant that lived throughout Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene and Holocene.

The skeleton of the straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus). Image credit: Ivo Verheijen, Schöningen Research Station.

The 300,000-year-old skeleton of a female straight-tusked elephant was found at the famous Pleistocene site at Schöningen, Lower Saxony, Germany.

The site is best-known for the discovery of wooden spears, the butchered remains of horses and other large mammals, and the remains of saber-toothed cats (Homotherium latidens).

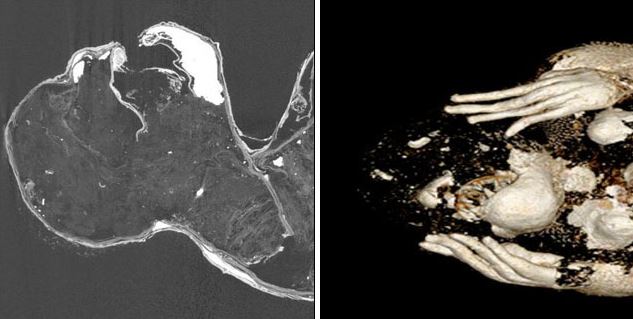

“We found both 2.3-m-long tusks, the complete lower jaw, numerous vertebrae and ribs as well as large bones belonging to three of the legs and even all five delicate hyoid bones,” said Dr. Jordi Serangeli, an archaeologist in the Senckenberg Centre for Human Evolution and Palaeoenvironment at the University of Tübingen.

“The elephant is an older female with worn teeth,” added Ivo Verheijen, an archaeozoologist at Leiden University.

“The animal had a shoulder height of about 3.2 m and weighed about 6.8 tons — it was therefore larger than today’s African elephant cows.”

“It most probably died of old age and not as a result of human hunting. Elephants often remain near and in water when they are sick or old,’ he added.

“Numerous bite marks on the recovered bones show that carnivores visited the carcass.”

“However, the hominins of that time would have profited from the elephant too.”

Reconstruction of the Schöningen lakeshore as the humans discovered the carcass of the straight-tusked elephant. Image credit: Benoit Clarys.

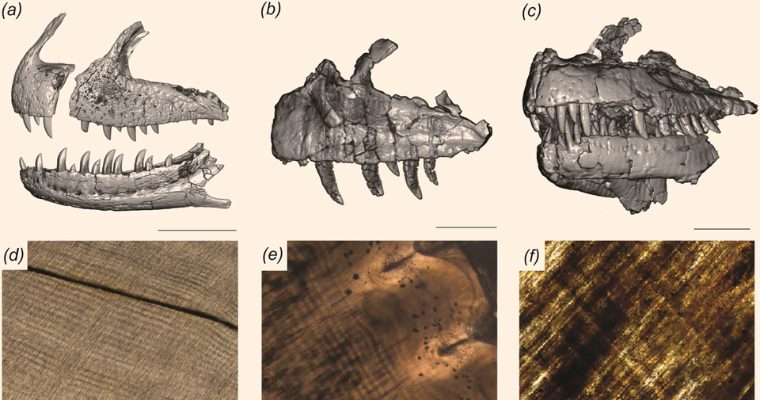

The archaeologists found 30 small flint flakes and two long bones which were used as tools for knapping.

They also found micro flakes embedded into these bones, which proves that resharpening of stone tools took place near to the elephant remains.

“Stone Age hunters probably cut meat, tendons and fat from the carcass,” Dr. Serangeli said.

“Elephants that die may have been a diverse and relatively common source of food and resources for Homo heidelbergensis.”

“Although the Paleolithic hominins were accomplished hunters, there was no compelling reason for them to put themselves in danger by hunting adult elephants,” he said.

“Straight-tusked elephants were a part of their environment, and the hominins knew that they frequently died on the lakeshore.”

“With the new find from Schöningen we do not seek to rule out that extremely dangerous elephant hunts may have taken place, but the evidence often leaves us in some doubt.”

Source: sci.news