A newly discovered asteroid called 2023 DW has generated quite a buzz over the past week, due to an estimated 1-in-670 chance of impact on Valentine’s Day 2046. But despite a NASA advisory and the resulting scary headlines, there’s no need to put an asteroid doomsday on your day planner for that date.

The risk assessment doesn’t have as much to do with the probabilistic roll of the cosmic dice than it does with the uncertainty that’s associated with a limited set of astronomical observations. If the case of 2023 DW plays out the way all previous asteroid scares have gone over the course of nearly 20 years, further observations will reduce the risk to zero.

Nevertheless, the hubbub over a space rock that could be as wide as 165 feet (50 meters) highlights a couple of trends to watch for: We’re likely to get more of these asteroid alerts in the years to come, and NASA is likely to devote more attention to heading off potentially dangerous near-Earth objects, or NEOs.

If a 50-meter-wide asteroid were to plunge through Earth’s atmosphere, it could create an airburst with as much power as a nuclear bomb. Such an blast, known as the Tunguska event, took place over Siberia in 1908, leveling hundreds of thousands of acres of remote forest land. A similar smashup in just the wrong place could destroy a city. It wouldn’t be as deadly as the cosmic impact that killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, which is thought to have been caused by an asteroid 6 to 10 miles wide, but it could spark a global emergency.

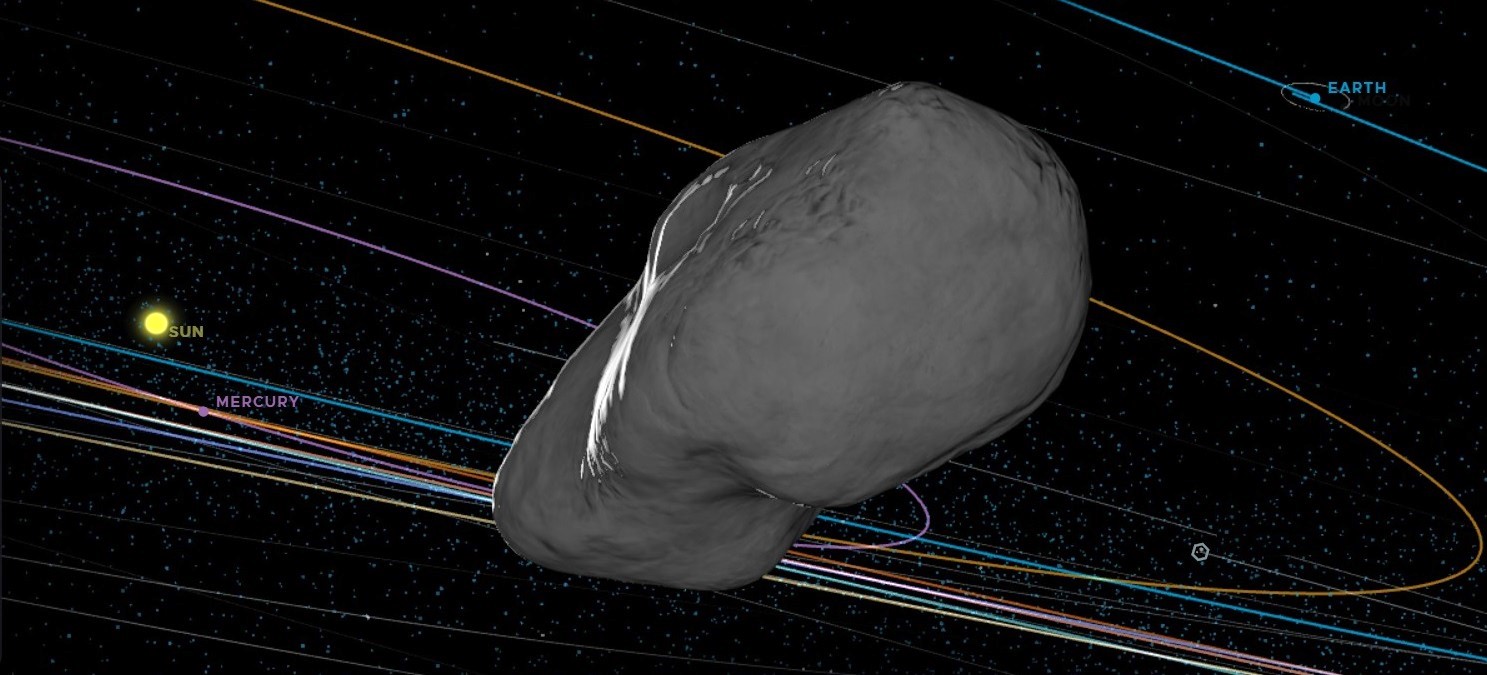

An asteroid search program that’s based in Chile’s Atacama Desert discovered 2023 DW in February, and some of the projections of its trajectory intersected with Earth’s orbit on Feb. 14, 2046. Its size — described variously as being as big as an Olympic swimming pool, the Leaning Tower of Pisa or 27 pandas — was estimated based on its brightness.

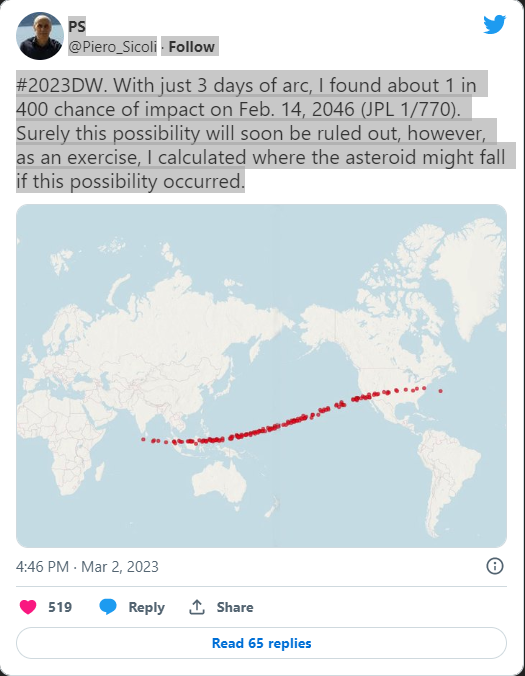

NASA took the sighting seriously enough to give it a 1 on the 1-to-10 Torino scale, which is used to rate the risks of near-Earth objects. 2023 DW is currently the only object to have a non-zero rating. Some went so far as to chart where the asteroid might strike if it hit Earth. (The possibilities range across a line extending from just off the southern tip of India to just off the U.S. East Coast.)

Astronomers emphasized that the risk assessment, which stands at 1-in-670 today, is based on a highly limited amount of data about the asteroid’s orbit around the sun. That uncertainty is visualized as an “error ellipsoid,” with Earth somewhere within the elongated egg-shaped zone of uncertainty.

“Often when new objects are first discovered, it takes several weeks of data to reduce the uncertainties and adequately predict their orbits years into the future,” NASA explained in a series of tweets.

The more observations you accumulate, the smaller the error ellipsoid becomes. And it often turns out that astronomers can identify a newly discovered asteroid in archived observations, providing more data points for refining their orbital projections. What typically happens is that the error ellipsoid eventually shrinks to a size that leaves out Earth.

If the risk assessment changes significantly in the weeks ahead, we’ll update this item to reflect the change. In the longer term, brace yourself for asteroid alerts of this level to become more routine.

When the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile begins a wide-angle survey of the sky in 2024 or so, it’s expected to identify thousands of potentially hazardous asteroids. NASA’s NEO Surveyor mission, planned for launch in 2028, will also add substantially to the asteroid count. A cloud-based data analysis technique pioneered at the University of Washington with support from the Asteroid Institute and the B612 Foundation could streamline the tracking process — and make it easier to distinguish the near-misses from the genuine threats.

What if a genuine threat is detected? NASA and the European Space Agency are already looking into ways to divert a more-than-potentially threatening asteroid. Last year, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test showed that an impacting spacecraft could alter an asteroid’s orbit, and a follow-up ESA mission called Hera will quantify the effect more precisely.

By the time 2023 DW shows up for its Valentine’s Day date in 2046, the world’s space agencies and policymakers should know what to do in case the close encounter threatens to get hot and heavy.

While serving as MSNBC.com’s science editor in 2011, Alan Boyle was part of the Near-Earth Objects Media/Risk Communications Working Group for a report that was prepared by the Secure World Foundation and the Association of Space Explorers and made available to the U.N. Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.

Source: universetoday.com