There’s a lot of matter in the Universe, but not all of it is visible to us. Matter is, essentially, anything that has mass and takes up space. That includes us, the planets, stars, nebulae, and galaxies. It also includes dark matter. It’s all spread out through space.

Is matter distributed evenly or is it grouped in clumps? Or could it be in some other configuration? To answer those questions specifically, astronomers map matter and compare it to theoretical models of the Universe. How do they do that? The first step is to build telescopes and use them to make observations and collect enormous amounts of data about the observable Universe. The measurements for matter distribution require specialized instruments that detect faint signals from distant reaches of the cosmos.

A research team from the University of Chicago and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory used two different telescopes and data from a space observatory called Planck to make the most up-to-date map of matter in the Universe. The result of their observations is this: matter in the Universe is not as clumpy as their models predict. That is, it’s not completely evenly spread out, which means it’s still somewhat clustered more in some areas than others. While that doesn’t sound very precise, it’s a huge step forward in knowing about the distribution of all the cosmic “stuff” that makes up our Universe.

The story of matter distribution began at the moment of the Big Bang, some 13.7 billion years ago. At that moment, all the matter was created. Since then, it’s been spreading out as the Universe expands. As it does, matter cools and clumps together. That clumping means that the Universe isn’t necessarily spread out smoothly. We can see that in the massive congregations of galaxies into today’s clusters and superclusters.

A full-sky map from the Planck mission shows matter as seen from Earth out to the limits of the observable Universe. Regions with less mass show up as lighter areas while those with more mass are darker. Courtesy ESA/Planck Mission.

Astronomers can detect distribution “clumping” in the early universe, too. They do it by looking at fluctuations in the microwave background radiation. That’s the very faint light from the Big Bang that is redshifted into the microwave part of the spectrum. The Planck mission measured temperature variations across this microwave background, which was not completely smooth and uniform. That light is the first emitted after the Cosmic Dark Ages, when the Universe was still too hot and filled with plasma to allow light to propagate. When light finally could get through (as things cooled down), that was the moment of Cosmic Dawn.

As time went by and the universe continued to expand and cool, and matter began clumping, the fluctuations grew denser and more massive with the pull of the matter’s gravity. Eventually, the first stars, galaxies, and other structures were born. So, the evolution of matter distribution from the earliest moments of the Universe to the richness of what we see now leads to questions about just how that distribution changed over time.

How Matter Got Mapped

The research team combined data from two major telescope surveys of the Universe to get this result. One is the Dark Energy Survey. It maps the existence and distribution of the unseen and mysterious dark matter that permeates the Universe. The other survey comes from the South Pole Telescope. It looks for faint radiation traces given off during the first moments of the Universe. The team also used data from the Planck mission, which studied the cosmic background radiation from the Big Bang.

The newly released survey of all the matter in the universe uses data taken by the Dark Energy Survey in Chile (above) and the South Pole Telescope. Credit: Andreas Papadopoulos.

Both efforts used gravitational lensing, which bends light as it passes by (or through) areas of space with heavy gravitational fields. That includes galaxies as well as accumulations of dark matter. Both will heavily distort the path of light from more distant objects and events in the early Universe. Coupling data from both surveys actually helps map the existence of both regular matter as well as dark matter.

In addition, combining two different methods reduces the chance that errors in one form throw off the whole survey. “It functions like a cross-check, so it becomes a much more robust measurement than if you just used one or the other,” said University of Chicago astrophysicist Chihway Chang, one of the lead authors of the studies.

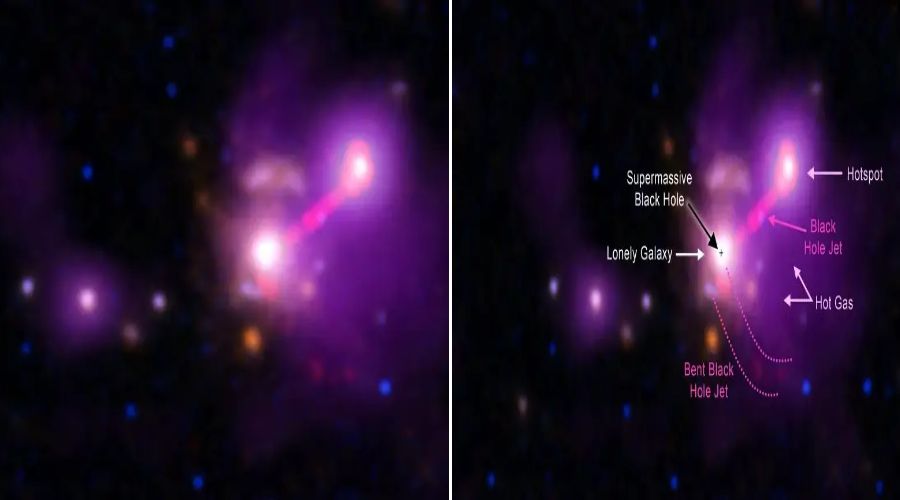

By comparing maps of the sky from the Dark Energy Survey telescope (at left) with data from the South Pole Telescope and the Planck satellite (at right), the team could infer how the matter is distributed. Courtesy: Yuuki Omori What it Means

Analysis of the data from both surveys let the scientists infer where all the matter in the Universe is now. More good news: the results fit perfectly with the currently best-accepted theory of the Universe. That’s not to say scientists now understand completely why the matter ended up where it is.

In fact, there’s a small problem. “It seems like there are slightly less fluctuations in the current Universe than we would predict assuming our standard cosmological model anchored to the early Universe,” said University of Hawaii astrophysicist Eric Baxter. Those fluctuations he’s referring to are the “clumpiness” of matter distribution. If you take into account all the physical laws governing the Universe and extrapolate them forward from the first moment of the Big Bang forward to now, the Universe should look slightly different than it actually appears to us now.

That doesn’t sound like a huge problem, but it could mean that there’s something missing from existing models of the Universe that astronomers will need to find. Still, the two surveys are a big step forward in understanding the distribution of matter. Not only do they show astronomers where matter is now, but they also mark a change in the way astronomers undertake such studies. “I think this exercise showed both the challenges and benefits of doing these kinds of analyses,” Chang said. “There’s a lot of new things you can do when you combine these different angles of looking at the Universe.”

Source: universetoday.com